There was a time when there wasn’t a single corner of Spain you couldn’t reach by train. With the improvement of road networks and the rise of cars, most of these railway tracks disappeared — but many have been transformed into greenways, exclusively for walkers and cyclists. What do they offer? Unique landscapes, routes far from busy roads, and most importantly, peace, quiet, and very gentle slopes.

La Camocha Greenway (Gijón, Asturias)

What landscapes does it connect, and what was it used for?

The Greenway starts in the southern outskirts of Gijón and links the city with the former coal mining site and extraction shafts of La Camocha, located seven kilometres away. The old railway line was used to transport the tons of coal extracted from the mines to the port of El Musel in Gijón.

What’s its history?

It had a short but intense history. It was created in 1949, when the mine had already been operating for about 15 years, and closed in 1986, when road transport replaced rail. Many of the 29 million tonnes of coal extracted here travelled along this path, now paved and bordered in many sections, which welcomes both cyclists and walkers today.

Why walk or cycle it?

- Because it offers a complete route from industrial Gijón to its rural surroundings, showcasing its social and scenic diversity: from palaces like the Duquesa de Riansares’ residence to traditional Asturian farmhouses — such as La Rubiera — with their granaries and bread barns, not to mention the headframes of La Camocha’s mine shafts.

- Because it’s a journey into Gijón’s mining past — a recent chapter of its history: in fact, less than 20 years have passed since La Camocha mine closed in 2007.

- Because once at the mine, the route can be extended by following the Llantones River Trail (heading north) or the Piles River Trail, through lush riverside forests all the way to the gates of Gijón.

Pas Greenway (Cantabria)

What landscapes does it connect, and what was it used for?

You could say it links two of Cantabria’s most vibrant worlds: the coastal area and the Pasiego valleys. It connects Astillero, a former industrial town on Santander Bay, with Ontaneda, in the heart of the Valles Pasiegos. Along its 34-kilometre route, you’ll leave behind an industrial, urban landscape to enter idyllic scenery of rural Cantabria — salmon rivers, green pastures where livestock graze, and mountains… lots of mountains.

What’s its history?

Created in 1902 to connect Santander with Burgos through the Pas River valley, the railway never went beyond Ontaneda, on the edge of Cantabria. Several reasons prevented its extension beyond this point, the main one being the construction of the Santander-Mediterranean broad-gauge railway. Even so, the Pas train operated until its final closure in 1973, serving the residents of the Pas and Pisueña river valleys.

Why walk or cycle it?

– Because it’s 34 kilometres of absolute disconnection and true luxury: a quiet trail away from the noise of the world, perfect for cycling or walking in total peace.

– Because it runs through an incredible variety of tourist attractions in Cantabria, rich in culture and nature:

- 19th-century spa towns like Puente Viesgo.

- Medieval landmarks like the collegiate church of Santa Cruz de Castañeda, with its beautiful Romanesque church and valuable Gothic artworks inside.

- Prehistoric caves with cave art on Mount Castillo, near Puente Viesgo, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site: Las Monedas, El Castillo, Las Chimeneas, and La Pasiega.

- Natural spaces like the Peña Cabarga Massif Natural Park, the riverside forests running alongside the greenway, and the steep Pasiego meadows that appear as you follow the Pas River upstream.

Compostela-Tambre-Lengüelle Greenway (A Coruña, Galicia)

What landscapes does it connect, and what was it used for?

This 29-kilometre section belongs to the former railway line that connected A Coruña with Santiago de Compostela. It’s a route through a deeply rural Galicia, subtly removed from the region’s main road networks. The old railway runs parallel to the Tambre and Lengüelle rivers, whose winding meanders guarantee beautiful riverside scenery throughout almost the entire route.

What’s its history?

Despite linking two of Galicia’s most important cities, this railway had a troubled history: more than 50 years passed between the initial project planning in 1864 and the start of construction works. Technical difficulties building on Galician terrain, along with the Spanish Civil War, delayed the opening until 1943. The last train ran in 2011, giving way to the current greenway — a route where all those past efforts now allow today’s walkers and cyclists to enjoy this unique trail.

Why walk or cycle it?

- Because it offers the chance to explore a genuine and little-known part of Galicia, close to two major urban centres, passing through the municipalities of Oroso, Ordes, Tordoia and Cerceda, along the longest greenway in Galicia.

- Because the entire greenway offers an unbeatable balcony over the extraordinary riverside landscapes of the Lengüelle River, along a surface of asphalt and compacted earth, alternating clearings and shadows in the forest with pasture and farmland.

- Because of its charming restored train stations, which evoke another era and another way of travelling.

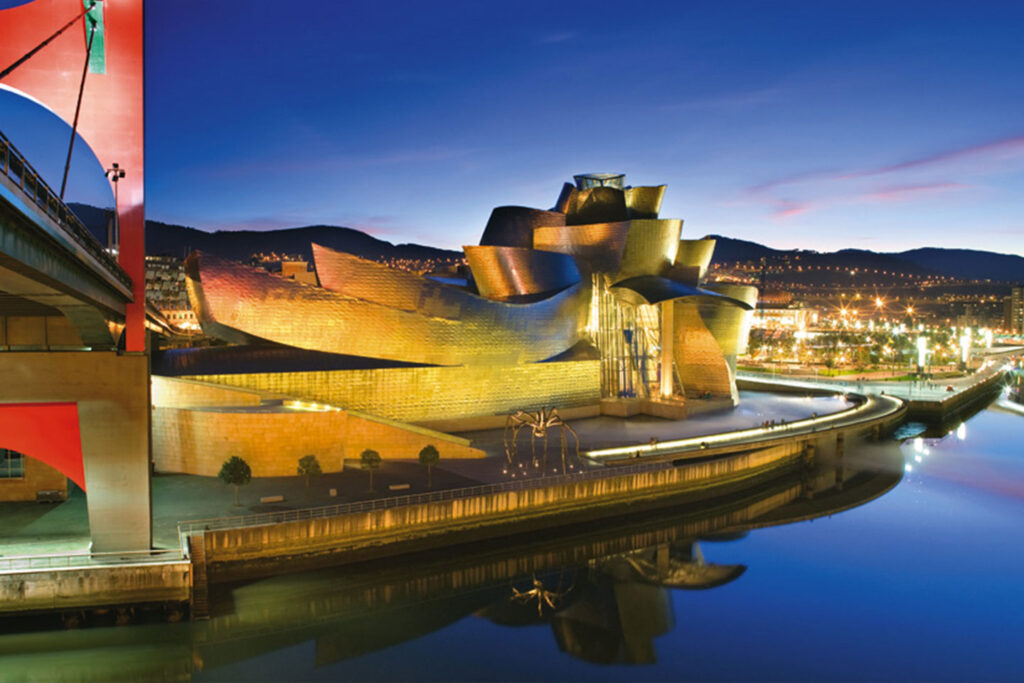

Montes de Hierro Greenway (Bizkaia, Basque Country)

What landscapes does it connect, and what was it used for?

This route is a literal journey into the heart of Greater Bilbao and the mining heritage that fuelled the famous Altos Hornos de Vizcaya steelworks, which shaped the industrial identity of this part of the Basque Country for decades. The Montes de Hierro Greenway combines two existing routes: Itsaslur/Campomar and Galdames (or La Galdamesa), connecting the region of Las Encartaciones with the coast. It stretches for almost 40 kilometres, from Traslaviña to the neighbourhood of Pobeña in Muskiz, the perfect final stop. The former railway line was used to transport iron ore from the heart of Las Encartaciones to the loading docks on the coast.

What’s its history?

In 1876, the British company Bilbao River Cantabrian Rail opened 22 kilometres of railway linking the mining operations in Galdames with the docks of Sestao. The line carried not only ore from its own mines but also from neighbouring mining sites. Over time, the existence of this transport line encouraged miners to build their homes in the rugged terrain alongside the railway, giving rise to new neighbourhoods. In 1972, nearly a century after its creation, the mines’ declining profitability led to the dismantling of the railway.

Why walk or cycle it?

- Because it’s a unique way to discover the rural landscapes that witnessed the Industrial Revolution in this part of Bizkaia during the 19th and 20th centuries. What is now an idyllic valley once bustled with mining activity — still visible in the old ore loaders, calcination furnaces, and open-pit mines — slowly being reclaimed by nature.

- Because it lets you explore a lesser-known corner of the Basque Country, far from the typical tourist routes, with attractions such as El Pobal Ironworks, the Peñas Negras Mining Interpretation Centre, the mining village of La Arboleda, the dunes of La Arena beach, and the Triano mountains.

And simply for the pleasure of walking or cycling along one of Spain’s most scenic former railway routes: the Itsaslur section, 3.5 kilometres of stunning coastal trail, where the mining train once transported ore from Kobaron to the washing plant and loading dock of Campomar, operated by the Mac Lennan company.